General AI is a game for the minority, while specialized AI is an opportunity for the majority

History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes. — Mark Twain

The Eight-Figure Salary Era in Silicon Valley

In recent months, Silicon Valley has been shaken by a set of jaw-dropping numbers: top AI experts have received eight-figure multi-year compensation packages; Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, publicly complained that Meta was poaching their employees with $100 million signing bonuses.

This isn't science fiction—it's the reality of the 2025 AI talent war. AI expert salaries have officially entered the compensation bracket of professional athletes and Fortune 500 CEOs.

But behind these astronomical salaries lies a deeper reality: the number of AI research scientists globally who truly possess the capability to train state-of-the-art large language models is estimated to be fewer than 1,000. This scarcity is redefining the entire tech industry's talent value system.

The Democratization of Knowledge

Behind this game that seems to belong only to a few "AI aristocrats," a much broader opportunity is quietly unfolding.

While pre-training foundation models requires astronomical funding and extremely rare talent, the application and optimization of AI technology—particularly post-training—isn't as high a barrier as we imagine. Technologies that only a handful of top labs could master just two years ago are now accessible through open-source models, detailed tutorials, and rich community resources.

An experienced recommendation system engineer, a business expert familiar with data mining, or even a domain expert in a vertical field—they can completely master large model post-training techniques within a few months and apply them to the business scenarios they know best. More importantly, their deep understanding of specific domains and insights into unique data are often more valuable than researchers who focus solely on general models.

The democratization of knowledge means that true competitive advantage no longer comes from monopolizing pre-training technology, but from understanding business, insights into data, and the ability to transform general capabilities into professional solutions.

Building Bridges from Traditional to Cutting-Edge

Based on these observations, I plan to write a series of articles exploring how to get started with post-training. If your background is in recommendation and search, and for various reasons you want to understand large models, particularly post-training, then you've come to the right place.

I'll explain the fundamentals of post-training from different angles, roughly divided into three parts, with several articles each:

History and Philosophy: This section will discuss the past and present of related technologies, such as the history of reinforcement learning, and the deep connections between post-training and recommendation/search. Consider these as stories.

Engineering and Practice: Through specific cases and experiments, demonstrating practical operations such as conversational style tuning (how to train an AI robot that speaks like a dubbed movie), value shaping (building AI "thought stamps" with different civilizational values from the Three-Body universe), and capability expansion (transforming dialogue models into reasoning models with thinking abilities).

Theory and Research: Knowing how is not enough; we must know why. After mastering basic operations, we can delve deeper at the theoretical level. From engineering to exploration. This section is for the more curious-minded.

The remainder of today's article is the first in the "History and Philosophy" series: by reviewing the development history of recommendation systems, we'll predict the future divergence trends of GenAI and explain why post-training is an important field that people with traditional technical backgrounds can enter.

Those Rankings We Chased Together

Veterans in recommendation and search might remember: In 2003, a dataset called MovieLens quietly emerged in academia. This small dataset containing 100,000 ratings from 943 users on 1,682 movies quickly became the "bible" of recommendation system research. Countless researchers experimented repeatedly on this dataset, pursuing those few decimal points of RMSE improvement, as if this were the entire essence of recommendation algorithms.

Subsequently, various academic competitions sprouted like mushrooms after rain: KDD Cup, SIGIR Cup, RecSys Challenge... Each attracted the world's top research teams. The academic circle back then was filled with a pure competitive spirit—everyone believed that excellent performance on these standardized datasets equated to success in the real world.

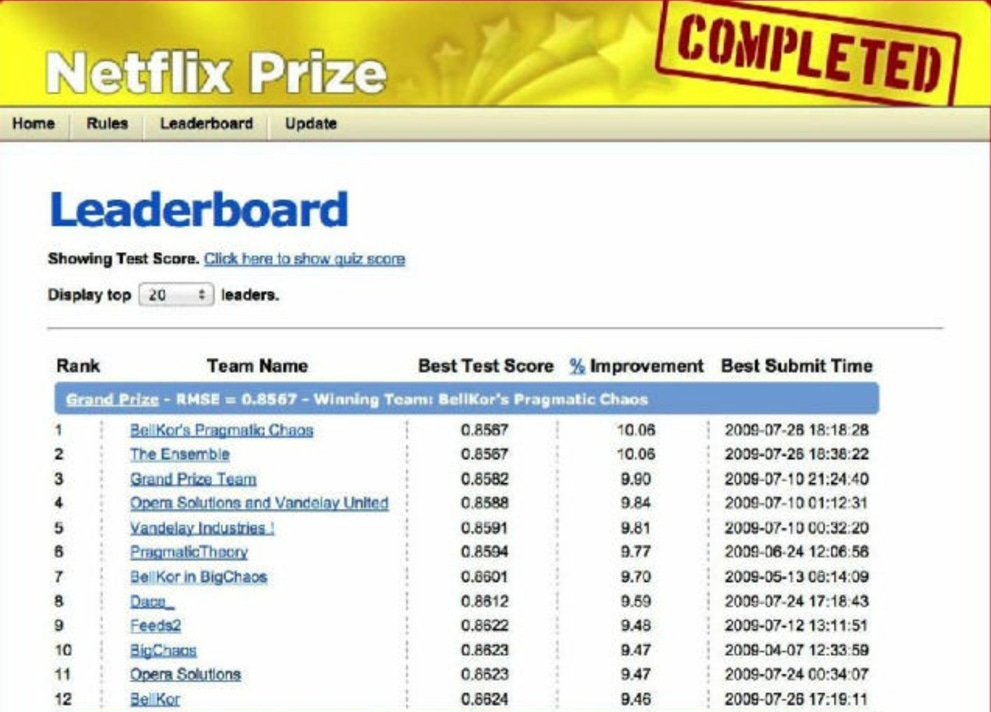

In 2006, Netflix pushed this competition to its climax. They offered a $1 million prize for an algorithm that could improve recommendation accuracy by 10%. A million dollars in 2006 was a fortune, attracting over 50,000 teams to participate in this three-year competition called the "Netflix Prize." Academia went crazy, with countless papers focusing on how to achieve better performance on this specific dataset.

However, the ending of the story was full of irony. When the winning team finally achieved the goal, Netflix made a surprising decision—they didn't deploy the winning algorithm. The reason was simple: the evaluation metrics looked impressive, but for various reasons, it couldn't be directly applied in practice.

The lesson from this story is profound: real-world value often differs drastically from performance on academic leaderboards.

History Repeating: From MovieLens to MMLU

Today's large model community is replaying this scene from the recommendation system field 15 years ago.

Looking back at the development of recommendation systems, we can see a clear evolutionary path: initially, academia was enthusiastic about comparing algorithm performance on public datasets like MovieLens and Amazon Product Reviews; later, the industry gradually realized that true competitive advantage came from deep understanding of their own product users' behavior and the value mining of unique data. Now, I basically won't read recommendation system papers without online testing.

Current LLM evaluation follows the same trajectory. MMLU, HellaSwag, HumanEval, GSM8K—these benchmarks are like the MovieLens of yesteryear, becoming targets for researchers to chase. Whenever a new model is released, the first thing is to check its performance on various leaderboards.

Llama, Claude, GPT, Gemini—everyone competes on these standardized tests, with researchers carefully tuning every parameter, pursuing those last few percentage points of improvement. Doesn't this scene seem familiar?

But just like recommendation systems back then, the significance of such comparisons is diminishing. Real value is beginning to shift toward players with unique data and deep cultivation in specific applications.

Pre-training: The Coming of the Oligopoly Era

The High Wall of Capital Threshold

If there's any pattern to technological development, it's that when costs reach a certain scale, the rules of the game fundamentally change.

Training GPT-4 reportedly cost over $100 million, and the industry generally predicts that next-generation model training costs could reach $1 billion or even higher. Computing power, data, and talent—each cost is prohibitively high.

Tesla actually open-sourced electric vehicle technology long ago, but the countries that can actually manufacture them can be counted on one hand. Pre-training is becoming a game for a few giants. Technical barriers aren't the biggest obstacle; the capital threshold to afford trial-and-error costs is.

Players You Can Count

Looking ahead a few years, companies that can continuously invest in foundation model training might truly be countable on your fingers:

China: ByteDance, Alibaba, Deepseek, Kimi, Tencent

USA: OpenAI, Google, Meta, Anthropic, xAI

Others: Perhaps Mistral can also get a seat at the table, Japan's Sakura AI leans more toward applications, Singapore's Reka AI founder Yi Tay has returned to Google

Just over ten companies constitute the core players in global foundation models. This concentration even exceeds that of the semiconductor or aerospace industries of the past.

Each company is investing in units of billions of dollars because they view AI as a strategic investment against other companies' monopolies. But for the vast majority of companies, training a foundation model from scratch has become an impractical choice.

This oligopolistic trend is, to some extent, capital-efficient. It concentrates resources in the hands of the most capable players, avoiding inefficient duplicate construction. But at the same time, it means control of AI infrastructure is in the hands of a few companies and two countries.

Post-training: From Oligopoly to the Warring States Period

The Divergence of Specialization

However, if the story ended here, it would be too boring. What's really interesting is what's happening in the post-training field.

Initially, everyone was confused about how to utilize foundation models. Many companies could solve their business problems by simply calling APIs. But soon, they discovered things weren't that simple.

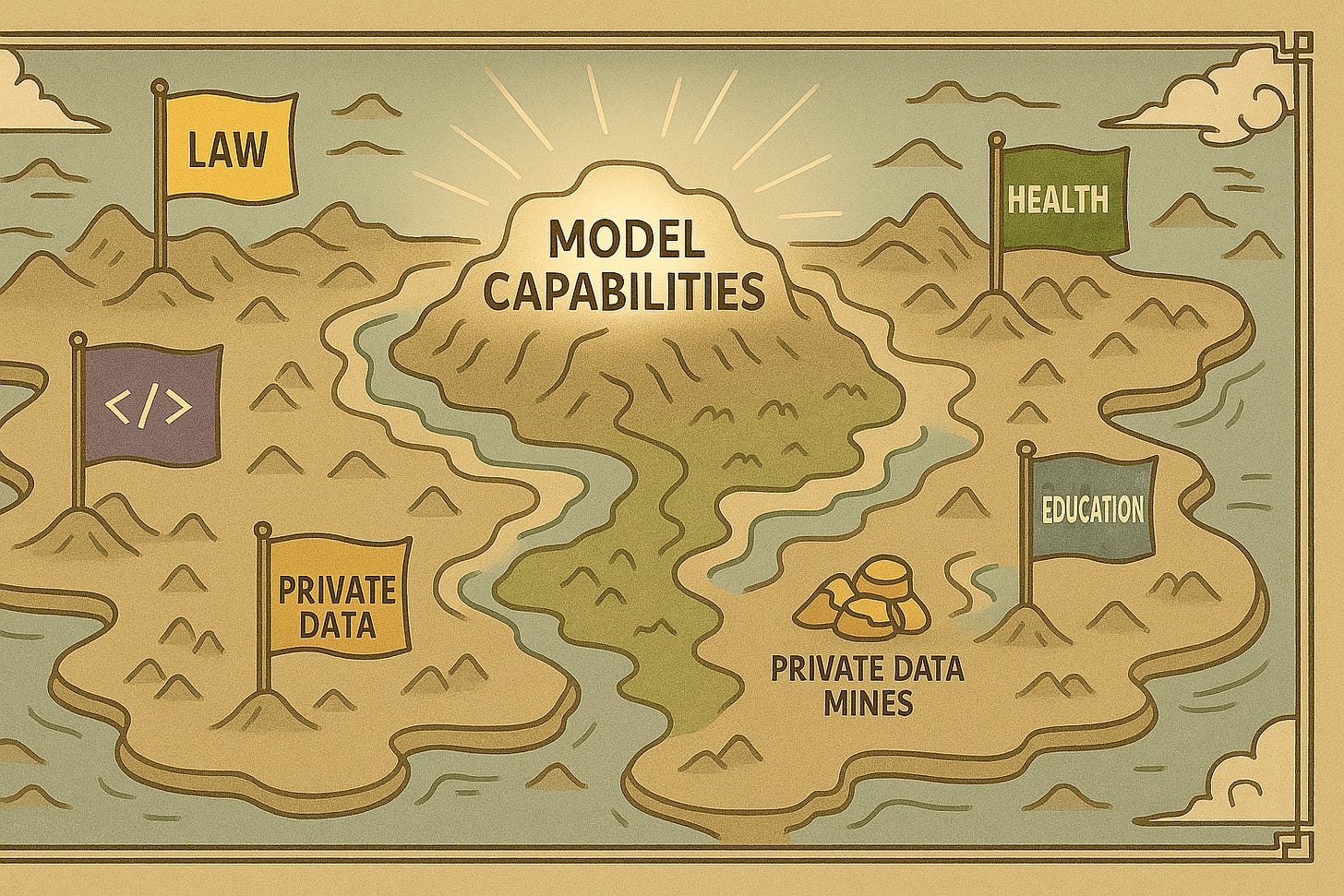

Real value is hidden in private domain data that cannot be made public or standardized:

Harvey AI's breakthrough in the legal field relies on massive legal cases, judgments, and internal law firm documents

Bloomberg's financial model BloombergGPT is based on decades of accumulated financial news, trading data, and analysis reports

Cursor's advantage in code generation comes from deep understanding of programmers' real workflows and carefully curated code data

Various professional AIs in the medical field depend on years of accumulated hospital case data, diagnostic records, and medical imaging

Each branch of scientific research is training specialized models based on domain-specific datasets

Even applications like virtual companions require large amounts of conversational data and emotional interaction records

This private domain data is the real moat. Unlike public domain data on Huggingface, it's not easily accessible, nor can it be obtained through simple crawling or purchasing. Data in each domain requires years of accumulation, professional annotation, and deep understanding.

Comparing Apples and Oranges

Under this trend of specialization, cross-domain model comparisons are becoming meaningless.

Which is better, YouTube's recommendation algorithm or Taobao's? The question itself is absurd. They serve different user groups, target different content types, and optimize for different business objectives. YouTube's algorithm value lies in finding suitable long videos for YouTube users, while Taobao's algorithm value lies in finding the best market matches for buyers and sellers.

Similarly, comparing whether Harvey AI's legal model or Cursor's code model is smarter is like comparing whether a cardiac surgeon or a pianist has more dexterous fingers—it's meaningless. They solve completely different problems and serve completely different user groups.

The Warring States Configuration

This trend of specialization has spawned an entirely new competitive landscape. It's no longer a head-on confrontation between a few giants on general capabilities, but professional competition in countless subdivided fields.

Each industry, each application scenario, might give birth to its own "mini-giant." They might not appear on general benchmark evaluations, but they're unbeatable in their professional domains. The core competitiveness of these companies lies not in computing power or model architecture, but in deep understanding of specific domains and accumulation of unique data.

This is a more diversified, more interesting competitive landscape. It means innovation is no longer monopolized by a few giants but distributed across various professional fields. Each field has its own rules of the game and its own success criteria.

The End of Involution

The Cessation of the Arms Race

The greatest benefit of this divergence is avoiding meaningless arms races.

When every company compares model performance on exactly the same datasets, it creates pure involution: everyone competes not on understanding user needs, but on who has more computational resources and better hyperparameter tuning skills. This competition is inefficient and unsustainable.

But when competition shifts to specialized fields, the situation changes. Medical AI companies don't need to compare whose model is stronger with gaming AI companies, and legal AI doesn't need to prove it's smarter than financial AI. Each field has its own evaluation standards and success metrics.

This divergence is actually a more rational allocation of resources. Instead of all companies crowding onto the same track, each finds the field they excel in most and cultivates it deeply.

The Continued Evolution of Pre-training

Of course, this doesn't mean competition in the pre-training field will stop. On the contrary, at the foundation model level, competition might become even more intense. Because these models need to provide powerful foundational capabilities for various specialized applications.

But the nature of this competition has changed: it's no longer direct comparison on standard benchmarks, but indirect competition in practical applications. Whichever foundation model can better support various downstream applications will gain more market share.

From General to Specialized: Redefining Value

This transformation from general competition to specialized division of labor is actually a sign of technological maturity.

In the early stages of any technological field, there's always a "grand unification" fantasy: believing there exists an optimal solution that can solve all problems. But as technology develops and applications deepen, people gradually realize that different application scenarios require different solutions.

This was true for recommendation systems, search engines, databases, and now AI.

In this new landscape, the definition of value is also changing. It's no longer about who has stronger general capabilities, but who can better solve specific problems.

An AI that can help doctors accurately diagnose diseases might be worth far more than a general model that performs excellently on various benchmarks. A code assistant that can significantly improve programmer productivity is more practically meaningful than an AI that wins mathematics competitions.

This shift in values also reflects the fundamental purpose of technological development: not to create stronger technology, but to solve real problems and improve people's lives.

Opportunities in the New Era

The Separation of Infrastructure and Applications

The future AI ecosystem might present a structure similar to cloud computing: a few major companies provide basic model services, while massive innovation happens at the application layer.

Pre-training models will become infrastructure providers like AWS and Google Cloud. They provide powerful but general capabilities, just as cloud service providers offer computing, storage, and network resources. Real value creation will happen in application-layer innovation built on these foundational capabilities. These providers will launch various post-training platform services.

This division of labor is reasonable and inevitable. Let the few capable companies focus on providing the best foundation models, and let more companies focus on applying these models to specific business scenarios.

The New Value of Data

In this new ecosystem, the value of data will be redefined. It's no longer about who has more general data, but who has more valuable specialized data.

A hospital with ten years of medical diagnostic records, a law firm with accumulated legal cases, an internet company with detailed user behavior records—their data advantages might be more valuable than any general dataset.

This change also means that the democratization of AI isn't achieved by enabling everyone to train GPT, but by enabling everyone to fully utilize AI capabilities in their professional fields.

Looking Forward: Embracing the Era of Divergence

From the history of recommendation systems, when a technological field transitions from general competition to specialized division of labor, it's often when it truly begins to generate enormous value.

When recommendation systems moved away from leaderboard competition and began diving deep into specific fields like e-commerce, social media, and content, they gave birth to commercial miracles like Amazon, Netflix, and TikTok.

Today's AI is heading down the same path. When we stop obsessing over improving a few percentage points on MMLU and focus on solving real problems in medical, legal, educational, and research fields, AI's true value will emerge. The former is the large model's test score; the latter is its actual capability.

The development history of recommendation systems tells us that the transition from general competition to specialized division of labor is the inevitable path of technological maturity.

Today's AI is repeating this journey. The oligopolization of pre-training and the Warring States period of post-training aren't a regression in technological development, but a sign of technological maturity. It means AI is transforming from a research field to an application tool; from pursuing general intelligence to specialized services.

When one door closes, another opens. The door to pre-training might be closing for most people, but countless doors to post-training are opening for those who are prepared.

This is the era we're entering: a new AI epoch where oligopolies coexist with numerous players, concentration dances with dispersion, and general runs parallel with specialized. The wheel of history rolls forward—from recommendation systems to GenAI, what changes is the technology, what remains unchanged is the pattern. And those who can read history and grasp the patterns will find their own opportunities in this new era.