If You Lived Life, You've Already Learned Reinforcement Learning (Part III)

Knowledge is the beginning of action, and action is the completion of knowledge. — Wang Yangming

This is the fourth article in our series on post-training for large language models, and the final installment of "If You Understand Life, You've Already Mastered Reinforcement Learning."

In our first article, "[General AI is a Game for the Few, Specialized AI is an Opportunity for the Many]", we analyzed the bifurcation happening in the AI industry: Pre-training is becoming oligopolistic, while Post-training is entering its own Renaissance. Every vertical domain has the opportunity to birth its own "mini-giants," with true competitive advantage coming from deep understanding of specific businesses rather than monopoly over general technology.

In the second article, "[If You Lived Life, You've Already Learned Reinforcement Learning (Part I)]", we explored the Bellman equation—the "mathematical principle of value judgment." It elegantly answers the philosophical question "what is worth pursuing": the value of a state equals immediate reward plus the discounted value of future states.

In the third article, "[If You Lived Life, You've Already Learned Reinforcement Learning (Part II)]", we delved into two fundamental questions in reinforcement learning: 1) How do we learn from mistakes? 2) When should we explore the unknown versus exploit the known? Through TD learning and Q-learning, we understood how to learn from feedback. Through ε-greedy strategy, we saw how to leave a branch for the unknown to grow on the trunk of rationality.

In this final installment, we'll briefly touch upon another crucial aspect of reinforcement learning: from ε-greedy's simple switch to Boltzmann's intelligent regulation; from value methods that "evaluate then act" to policy methods that "learn preferences directly through action"; from REINFORCE's pioneering path to PPO's engineering wisdom. We'll glimpse how reinforcement learning evolved from indirect to direct, from theoretical to practical, ultimately laying the foundation for understanding the RLHF technology behind ChatGPT.

When Simple Switches Meet Complex Gym Choices

Imagine you've been working out for three months. This afternoon, you're standing in the gym again, facing that familiar dilemma: should you train your strongest muscle group—chest (perfect form, satisfying gains), challenge the leg day you've been avoiding (exhausting but effective), or try some functional training you've never done before?

Following the ε-greedy logic from our previous article, you'd either spend 85% of your time on chest or 15% of your time making completely random choices—maybe legs today, swimming tomorrow. But what would you actually do in real life?

You'd adjust based on your current state: when energized, you're more willing to tackle high-intensity leg training; when tired, you choose relatively easier upper body work; when in a good mood, you try new training methods. This isn't a rigid probability switch—it's a continuous adjustment of preferences.

The Fundamental Limitation of ε-Greedy

While ε-greedy is simple and effective, it has a fundamental problem: overly crude binary switching. It reduces the world to "optimal" versus "everything else," choices to "rational" versus "random."

In fitness training, this simplification creates two problems:

When multiple exercises are valuable: Chest training scores 9.1, back training 9.0, shoulder training 8.9. ε-greedy would have you train chest 90% of the time, all because of a 0.1 difference.

When the gap is significant: Chest training scores 9.0, leg training 6.0, random flailing scores 1.0. ε-greedy gives leg training and random flailing the same "exploration" probability, which is clearly absurd.

Real fitness is more like intelligent allocation based on exercise value, not simple on-off switching.

When Simple Switches Meet Complex Gym Choices

Imagine you've been working out for three months. This afternoon, you're standing in the gym again, facing that familiar dilemma: should you train your strongest muscle group—chest (perfect form, satisfying gains), challenge the leg day you've been avoiding (exhausting but effective), or try some functional training you've never done before?

Following the ε-greedy logic from our previous article, you'd either spend 85% of your time on chest or 15% of your time making completely random choices—maybe legs today, swimming tomorrow. But what would you actually do in real life?

You'd adjust based on your current state: when energized, you're more willing to tackle high-intensity leg training; when tired, you choose relatively easier upper body work; when in a good mood, you try new training methods. This isn't a rigid probability switch—it's a continuous adjustment of preferences.

The Fundamental Limitation of ε-Greedy

While ε-greedy is simple and effective, it has a fundamental problem: overly crude binary switching. It reduces the world to "optimal" versus "everything else," choices to "rational" versus "random."

In fitness training, this simplification creates two problems:

When multiple exercises are valuable: Chest training scores 9.1, back training 9.0, shoulder training 8.9. ε-greedy would have you train chest 90% of the time, all because of a 0.1 difference.

When the gap is significant: Chest training scores 9.0, leg training 6.0, random flailing scores 1.0. ε-greedy gives leg training and random flailing the same "exploration" probability, which is clearly absurd.

Real fitness is more like intelligent allocation based on exercise value, not simple on-off switching.

Boltzmann Policy: The Art of Intelligent Allocation in Fitness

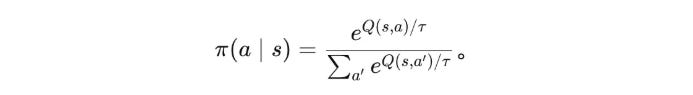

The Boltzmann policy offers a more elegant solution. Instead of hard-switching between "mastery or randomness," it transforms exercise value into continuous time allocation. (We can ignore the equation for now)

If ε-greedy is like a two-position switch, Boltzmann is like a graduated dial. The key is the temperature parameter τ—not just a mathematical parameter, but an embodiment of training mindset.

Training State as Temperature

Let's continue our gym example. After three months of training, you've rated each muscle group: chest training (proficiency 10), back training (8), leg training (6), new exercises (4).

When preparing for competition (high pressure, low τ):

Your attention highly focuses on the "safest" exercises

Even small proficiency differences amplify into huge time allocation differences

Like pre-competition training where you only practice your most confident moves, no room for risk

During regular training (relaxed state, high τ):

You're more willing to give "weak areas" more training opportunities

Differences between exercises flatten out, training time allocation becomes more balanced

Like recreational fitness where you develop all muscle groups comprehensively

Let's look at specific numbers. With Q-values of 10, 8, 6, and τ=2:

Notice this intelligent allocation: the most proficient area gets over half the time, but other areas all receive reasonable training opportunities—even the most challenging new exercises retain over a tenth of the time.

The Life Philosophy of Temperature

τ → 0 (Focus Mode): Almost exclusively train the most proficient areas. This is "focus mode," suitable for competition prep, photoshoots, or situations requiring peak performance display.

τ → ∞ (Comprehensive Mode): Each area receives similar training time. This is "comprehensive mode," suitable for daily fitness and well-rounded development phases.

Progressive Adjustment: As overall skill improves, you can lower temperature to focus more on strengths; when hitting plateaus, raise temperature to increase attention to weaknesses.

Boltzmann policy captures the true rhythm of fitness: leverage strengths while addressing weaknesses, finding the wisest balance between specialization and comprehensiveness.

Why Take the Detour? The Learning Revolution from Indirect to Direct

But let's step back and think: whether ε-greedy or Boltzmann, they all follow the same logic:

First evaluate: Estimate each exercise's value through Q-learning

Then convert: Transform value into training time allocation through some policy

Finally execute: Choose specific exercises based on allocation ratios

This process seems reasonable, but think carefully—there's a fundamental problem: Why take such a big detour?

The Directness of Real Fitness

Think about how you actually learned to work out.

Value-based fitness learning:

First learn to evaluate each exercise's quality (establish value system)

Then design training plans based on evaluations

Every exercise choice requires first evaluating "how good is this?"

Actual fitness learning:

Directly feel your body's response and changes during training

Adjust training preferences based on effects and body sensations

Gradually form training habits that suit you

Which resembles real learning? Obviously the latter. True fitness experts don't evaluate then train—they directly embody their understanding of the body through training.

The Fundamental Limitation of Value Methods

All value-based methods share a common problem: indirectness. They assume we need to first know "how good this is" before deciding "what to do."

But this assumption breaks down in two situations:

1. When the training choice space is vast

Real fitness is often high-dimensional and continuous. Training weight, sets, rest time, range of motion—these can't be simply described with discrete states. Estimating value for every minute training combination becomes unrealistic.

2. When optimal strategy itself requires randomness

In some sports, predictability itself is a disadvantage. In combat training, if your combinations are too fixed, opponents can anticipate and counter. Here, "intentional variability" is high-level performance.

Value methods try to find the "best training combination," then add some randomness. But this is like using a "perfect training plan" to explain professional athletes' improvisation—always one step removed.

Policy Gradient: Let Skill Intuition Grow Naturally

Spend enough time in the gym, and you'll notice something interesting: some people don't check training plans.

They walk into the gym, and their body naturally tells them what to train today. Chest feeling fatigued? Naturally shift to back training. Legs feeling good? More leg work today. This intuition isn't innate—it comes from the body's precise perception of its own state after thousands of training sessions.

This is the philosophy of policy gradient: not making optimal choices within a fixed framework, but continuously rewriting the preferences themselves through training.

The Fundamental Divergence of Two Learning Philosophies

Let's revisit the two paths of learning:

Value methods: Evaluate exercise value → Design training plan → Execute training

Policy methods: Directly learn training preferences → Execute training

From three steps to two, from indirect to direct. This isn't just simplification of steps, but a fundamental shift in learning philosophy. Value methods are like rationalists—believing that through careful analysis and calculation, we can find the optimal solution. Policy methods are more like empiricists—trusting the body's wisdom, letting intuition grow naturally through practice.

The Training Intuition of Policy Gradient

Back to the gym. Traditional Q-learning is like adjusting selection probabilities from a fixed "training menu"—chest training worth 9 points so choose it more, leg training worth 3 points so choose it less. Policy gradient is rewriting the menu itself.

Week one, you might allocate training time evenly: chest 25%, back 25%, legs 25%, core 25%. This is the novice's naive strategy—know nothing, try everything.

After a week, your body provides feedback: chest training progressing rapidly (reward +3), back improving (reward +1), legs not recovered (reward -1), core training completely ineffective (reward -2).

Week two, your body naturally adjusts preferences: chest 35%, back 30%, legs 20%, core 15%. This adjustment is gradual, natural, like the formation of muscle memory—comfortable training reinforces tendency, painful training moderately downweights but doesn't abandon.

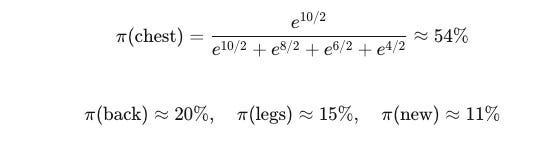

Mathematical Expression of Policy Gradient

This intuitive process can be precisely described mathematically:

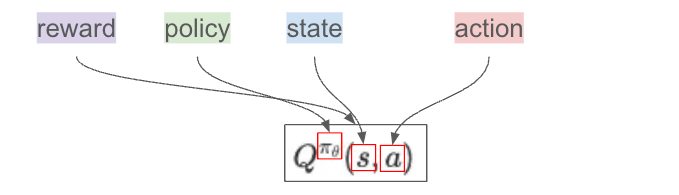

Don't be intimidated. Let's understand from right to left:

Layer One: The Reward Signal

This is asking "how effective was today's chest training?" If Q > 0, this action was better than usual; if Q < 0, the action was subpar. Where:

State s (blue) → Current environmental information. Like today's physical condition (energy level, muscle soreness).

Action a (red) → What you actually did in this state. Like which training to choose (chest, back, legs, core).

Reward Q(πθ, s, a) (purple) → Long-term benefit of the choice. The "score" for long-term effects of choosing this action with this training habit in this physical state.

Policy πθ (green) → The "rule" or "tendency" determining what action to choose in a state. Like your training allocation (chest 35%, back 30%, legs 20%, core 15%). This is actually a probability value between 0 and 1, representing how likely you are to choose action a in state s with policy parameters θ.

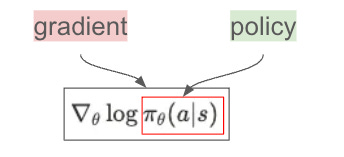

Layer Two: Policy Sensitivity

This scary-looking thing is actually just "how long is the lever for adjusting training preferences."

πθ(a|s): Already explained above.

∇θ: Gradient with respect to policy parameters θ, meaning: If we slightly adjust the recipe (proportions), how does the probability of choosing this action change?

Why logarithm? If a training method's selection probability changes from 0.1 to 0.2, versus from 0.5 to 0.6, both increase by 0.1, but the former doubles while the latter only increases by 20%. Logarithm captures this importance of relative change.

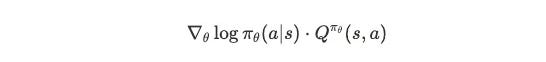

Layer Three: The Intelligent Learning Rule

Now combining both layers:

This product embodies policy gradient's core wisdom:

If training is effective (Q > 0): Adjust parameters in the direction of ∇θ log πθ(a|s), increase tendency to choose it

If training is ineffective (Q < 0): Adjust parameters in the opposite direction of ∇θ log πθ(a|s), decrease tendency to choose it

The more pronounced the effect (larger |Q|), the bigger the adjustment

Layer Four: Stability Through Expectation Eπθ[·]

The outermost expectation operator Eπθ ensures we're not misled by single training randomness. It tells us to adjust policy based on multiple training experiences, not be swayed by one good or bad day.

Three Advantages of Policy Learning

1. Direct Optimization: Value methods need "value estimation → policy selection" conversion, like first calculating each food's nutritional value before deciding what to eat. Policy methods directly optimize what we truly care about: how to choose better.

2. Natural Adjustment Process: Changes are gradual, no drastic habit mutations. Like the natural law of skill learning: good habits gradually strengthen, bad habits gradually fade, but won't completely change overnight.

3. Intelligent Attention Allocation: Important training experiences (major breakthroughs or setbacks) get more attention, routine training has less impact. This matches human learning patterns—we always learn most from extreme experiences.

REINFORCE: Policy Gradient's Pioneering Path

One concrete implementation of policy learning is REINFORCE.

Let's travel back to 1992, when deep learning was still in winter. Ronald J. Williams at Northeastern University, in a paper titled "Simple Statistical Gradient-Following Algorithms for Connectionist Reinforcement Learning," first proved something seemingly impossible: we can directly optimize the policy itself without detour through value functions.

This was revolutionary at the time. Conventional wisdom held that reinforcement learning must first evaluate "what is good" before deciding "what to do." Williams said: Why not directly learn "what to do"?

REINFORCE's Naive Wisdom

REINFORCE's core idea is extremely naive, so naive you might doubt it actually works:

I know you're frustrated with formulas, but this one has just two main parts:

Ri: Starting from state si, after executing action ai, the total reward until episode end. Not immediate reward, but "all benefits this choice ultimately brings."

∇θ part: We've seen this before—policy sensitivity to parameters, telling us how to adjust parameters to increase probability of choosing action ai.

Core logic: If total return from this training session was good (large Ri), increase tendency for this choice; if total return was poor (small Ri), decrease this tendency.

The naivety lies in: treating the entire training process as a "package"—either strengthen all or weaken all. Like rating a complex dish—you might not know which spice was key, but you know the dish was "overall good" or "overall bad."

REINFORCE's Fatal Weakness

But this naivety brings a fatal problem: enormous variance.

Imagine you did a compound training set at the gym: squats + deadlifts + bench press. After this round, you feel great (Ri = +5). But this "great" might come from:

The training method really works

You slept well today

You're in a good mood

Your new workout clothes boost confidence

The gym's music today is particularly energizing

REINFORCE attributes all credit to the training method, then significantly increases probability of choosing these exercises. Next day with the same method but poor sleep and bad mood, results are terrible (Ri = -3), and REINFORCE significantly reduces these exercises' weight.

This oscillating learning process makes REINFORCE theoretically correct but practically inefficient. Like an emotional person, easily swayed by single experiences.

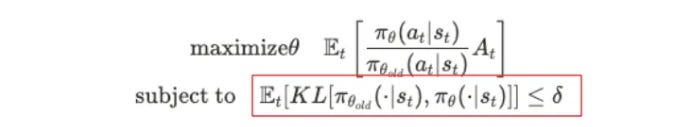

From TRPO to PPO: The Historical Leap to Stability

In 2015, John Schulman at UC Berkeley with his advisor Pieter Abbeel and OpenAI's Igor Mordatch published "Trust Region Policy Optimization," first systematically solving policy update stability problems.

TRPO's core idea: Don't let the new policy stray too far from the old policy. It introduces a mathematical constraint:

The key is in the red box. KL divergence measures difference between two policies, δ is a small number. Simply put: You can improve the policy, but not with too big a step.

TRPO is theoretically beautiful but has a practical problem: it requires computing complex second-order derivatives (Hessian matrix), computationally expensive and complex to implement. Like a high-performance supercar that's hard to maintain—theoretically beautiful, practically headache-inducing.

PPO: Engineering Wisdom in Simplicity

In 2017, John Schulman, now at OpenAI, led the team in publishing "Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms," proposing PPO—an algorithm "crude as dirt" but "ridiculously effective."

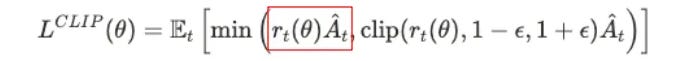

PPO's core insight: we don't need precise mathematical constraints, just a simple and brutal clipping function. PPO's formula looks complex, but let's break it down:

Don't be scared by the formula pile—the core is that small part in the red box, the rest are corrections and limits.

Layer One: Probability Ratio rt(θ)

This is the probability ratio between new and old policies. This ratio tells us: compared to the old policy, how much has the new policy's probability of choosing this action changed?

If rt(θ) = 2, the new policy's probability of choosing this action is twice the old

If rt(θ) = 0.5, the new policy's probability is half the old

Layer Two: Advantage Function Ât

This is the Advantage Function, answering a key question: compared to average, how good is this action?

In the fitness example:

If your usual post-workout feeling is 3 points, but today after squats you feel 5 points, then Ât = 5 - 3 = 2 > 0 (this choice is better than average)

If today after squats you feel 1 point, then Ât = 1 - 3 = -2 < 0 (this choice is worse than average)

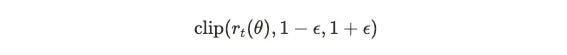

Layer Three: Clipping Function

This is PPO's innovation. The clip function limits the ratio to [1-ε, 1+ε], typically ε = 0.2:

clip(r, 0.8, 1.2) = {

0.8, if r < 0.8

r, if 0.8 ≤ r ≤ 1.2

1.2, if r > 1.2

}Layer Four: Meaning of E[min(...)]

E denotes expectation, min(...) means take the smaller value. PPO calculates two values at each moment:

rt(θ)Ât: Normal policy gradient update

clip(rt(θ), 1-ε, 1+ε)Ât: Clipped update

Then take the smaller value—this is key!

PPO's Intuitive Explanation

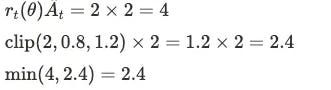

Let's understand this "take the smaller" wisdom through fitness:

Case 1: Good Actions (Advantage > 0)

Say yesterday's training plan was: chest 30%, back 30%, legs 25%, core 15%. Today after training, chest was particularly effective (At = +2), new policy wants to increase chest to 60%.

PPO says: Even if it's effective, don't change too much at once. Chest proportion can only increase to 36% max (30% × 1.2).

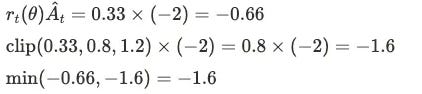

Case 2: Bad Actions (Advantage < 0)

If core training was terrible (Ât = -2), new policy wants to reduce core from 15% to 5% (rt(θ) = 0.33).

PPO says: Even if it's bad, don't cut too harshly at once. Core proportion can only decrease to 12% min (15% × 0.8).

This "conservative optimism" avoids drastic oscillations in training plans, making learning progress while maintaining stability.

PPO's Historical Significance and Impact

PPO's success exceeded everyone's expectations. After publication, it quickly became the de facto standard in the reinforcement learning community:

Victory of Engineering Simplicity: PPO proved a profound engineering philosophy—sometimes, a "less elegant" but practical solution is more valuable than mathematically perfect theory. Compared to TRPO's complex constraint optimization, PPO needs just a few lines of code.

OpenAI's Strategic Choice: OpenAI quickly made PPO their default internal algorithm. PPO then proved itself across various tasks: from Atari games to robot control, from dialogue generation to code writing. This widespread application in turn drove further optimization.

Academic Recognition: The PPO paper has been cited over 30,000 times, becoming classic literature in reinforcement learning. More importantly, it inspired a series of subsequent work, including various PPO variants and improvements.

Bridge to RLHF: In 2019, when OpenAI began exploring how to better align language models with human values, PPO became their tool of choice. The RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) technology behind ChatGPT is built on PPO's foundation.

In a sense, PPO isn't just an algorithm—it represents AI research's shift from "showing off" to "practical application." In this transition, Schulman and his team demonstrated a valuable quality: willingness to set aside academic perfectionism to solve real problems.

In Closing

We've only skimmed the surface of reinforcement learning's ocean. Many important concepts remain unexplored: how Actor-Critic architecture elegantly combines policy and value, how Monte Carlo Tree Search defeated humans at Go, and various advanced exploration strategies.

This trilogy serves merely as an introduction, hoping to spark initial interest in this field. As Newton said: "I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me."

This approach was chosen because it leads directly to our true destination—post-training of large models. There, RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback), based on algorithms like PPO, teaches ChatGPT to better understand human intent.

Reinforcement learning teaches us not just algorithms, but a way of thinking: how to make decisions under uncertainty, how to learn from failure, how to balance exploration and exploitation. This wisdom proves especially precious in the age of artificial intelligence.